Fed Acknowledges Limits in Fixing Inequality Linked to Its Own Policies

The US Federal Reserve has acknowledged that economic inequality in the country has widened in recent years — and some policymakers admit it is not a problem the central bank can easily resolve.

During the pandemic, the Fed slashed interest rates to historic lows to protect the economy from collapse. While the move stabilized markets and supported growth, it also allowed wealthier Americans to lock in ultra-low borrowing costs, purchase assets and build long-term wealth.

According to housing data, roughly one in five US homeowners still holds a mortgage rate below 3%, insulating them from today’s higher interest rates while benefiting from rising home values. At the same time, US stock markets continue to post strong gains, driven largely by technology and artificial intelligence investments.

Lower-income Americans, however, have not shared equally in these gains. Renters and households with limited access to investments have missed out on asset-driven wealth growth, while wage increases for lower earners have lagged behind those of higher-income workers throughout 2025, according to Federal Reserve data.

Affordability pressures — including housing, food and everyday expenses — have become a growing concern nationwide and a central issue in political debate. Despite this, Fed officials say their tools are limited when it comes to correcting what economists describe as a “K-shaped economy,” where wealthier households continue to advance while others fall behind.

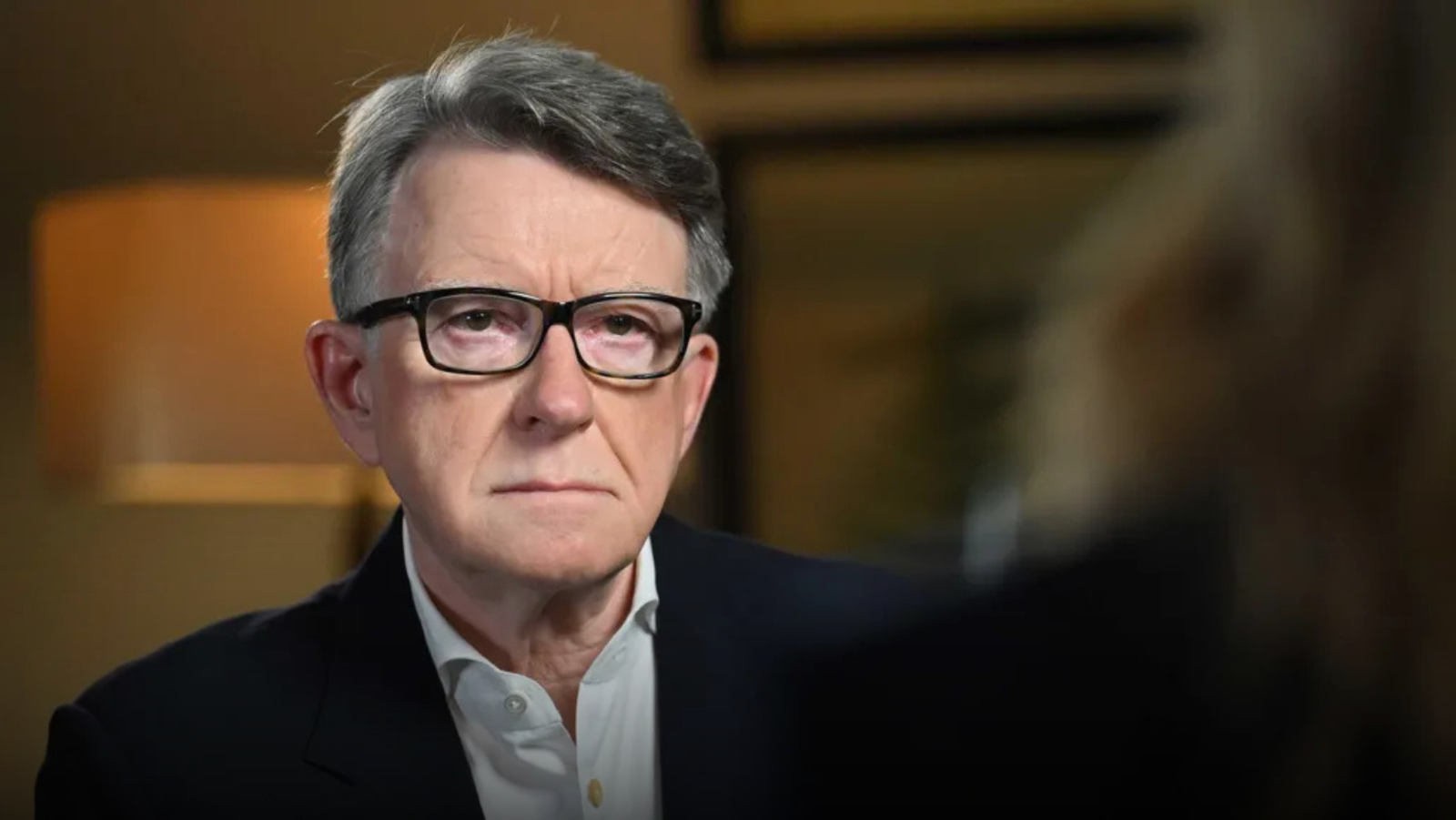

Speaking at a recent economic summit, Federal Reserve Governor Christopher Waller said consumer demand remains strong among higher-income groups, while lower-income households are increasingly struggling to keep up.

“The challenge is restoring broader job security and wage growth,” Waller said, adding that strengthening the labor market remains the Fed’s most effective path toward easing inequality.

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell and other policymakers have also acknowledged the widening gap this year, noting that monetary policy was never designed to directly manage wealth distribution.

Economists point out that the roots of the imbalance stretch back well before the pandemic. Large-scale stimulus measures following the 2008 financial crisis boosted asset prices, disproportionately benefiting those who already owned homes and stocks.

While the Fed has since raised interest rates sharply to control inflation, many economists believe the long-term effects of past policies will continue to shape inequality for years — well beyond the reach of central bank tools.