Landmark Rohingya Genocide Case Against Myanmar Heard at World’s Top Court

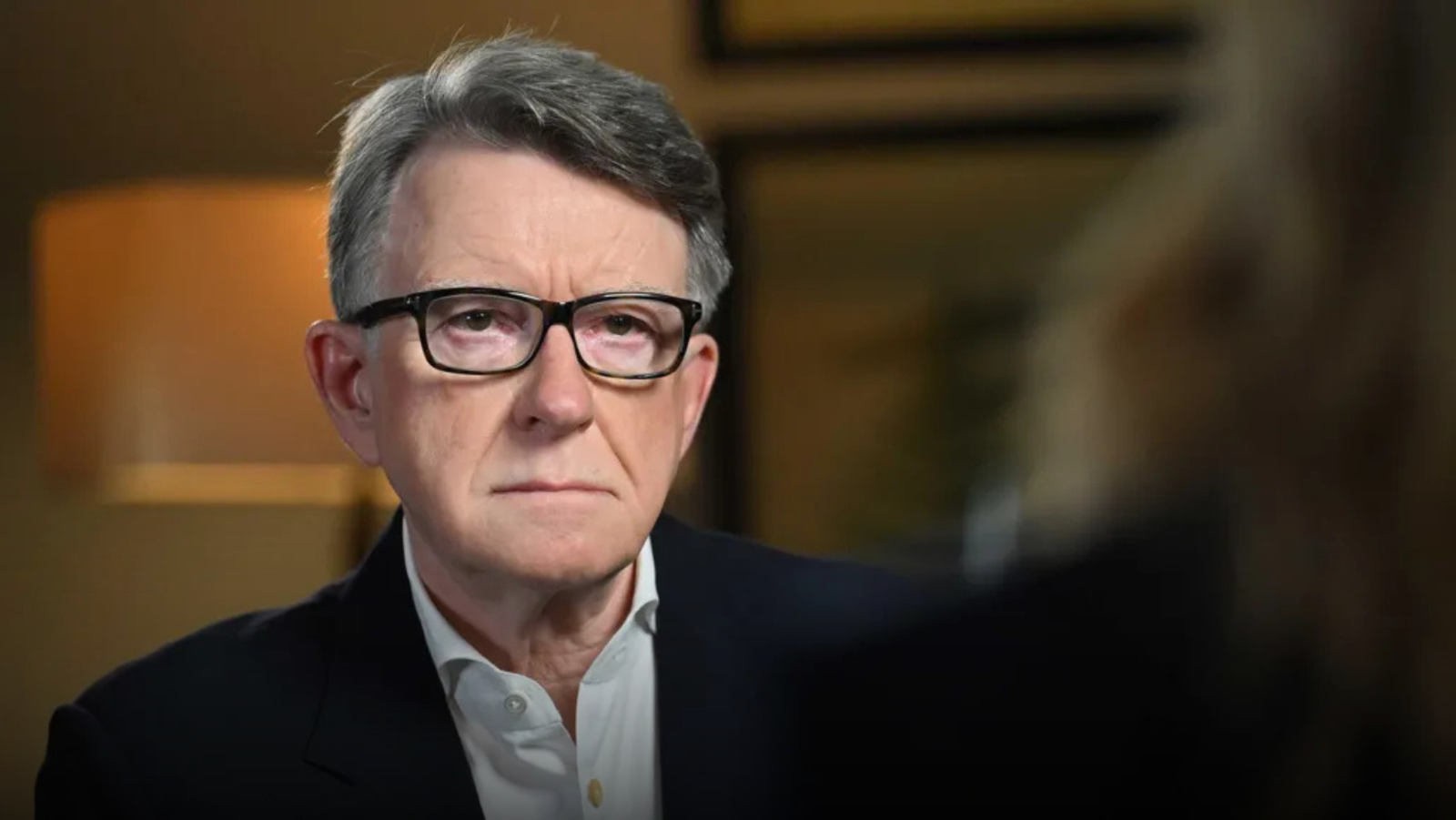

Myanmar pursued “genocidal policies” in an effort to erase the Rohingya people, The Gambia’s foreign minister Dawda Jallow told the world’s top court as judges began hearing a landmark case accusing the country of genocide.

The International Court of Justice is considering a lawsuit filed by The Gambia in 2019, alleging that Myanmar deliberately sought to destroy its Muslim minority population. Myanmar has consistently denied the accusations.

Jallow told the court that his government had reviewed “credible reports of the most brutal and vicious violations imaginable inflicted upon a vulnerable group,” adding that the Rohingya had suffered decades of persecution followed by a military campaign designed to eliminate their presence in the country.

Thousands of Rohingya were killed and more than 700,000 were forced to flee during a sweeping army crackdown in 2017, most seeking refuge in neighbouring Bangladesh.

A United Nations investigation in 2018 concluded that senior military leaders in Myanmar should be investigated for genocide in Rakhine state and crimes against humanity elsewhere. Myanmar rejected the findings, insisting its operations were aimed at militant threats rather than civilians.

Myanmar will have the opportunity to respond to the allegations during hearings that are expected to continue until the end of the month. The court has also set aside time to hear testimony from witnesses, including Rohingya survivors, although those sessions will be closed to the public.

A final ruling is not expected for months, and possibly years. While the court cannot prosecute individuals, its judgments carry significant political and legal weight within the United Nations system and beyond.

Jallow said The Gambia brought the case out of a sense of responsibility shaped by its own history under military rule. He said Myanmar now appeared trapped in a cycle of violence and impunity following the military’s seizure of power in 2021.

Myanmar’s former civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi, who was removed from office in the coup and later jailed, saw her international standing damaged after defending the army’s actions when earlier genocide accusations were raised.

Outside the court, Rohingya survivors called for accountability from Myanmar’s military leadership, saying justice had been delayed for too long.

More than one million Rohingya remain in refugee camps in Bangladesh’s Cox’s Bazar region, among the largest and most crowded in the world. Many others have risked dangerous sea journeys in search of safety in countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia.

Legal experts say the case could shape how future genocide claims are handled, as it is the first such case to be heard in more than a decade. Judges are expected to clarify how international law defines genocide under the 1948 UN Genocide Convention, which prohibits acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group.

Jallow said the convention’s words would mean little unless they were enforced, adding that The Gambia’s case is backed by dozens of countries, including members of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and several Western nations.

Alongside the proceedings at the International Court of Justice, the International Criminal Court is separately investigating Myanmar’s military ruler, Min Aung Hlaing, over alleged crimes linked to the treatment of the Rohingya.